18 years on Saturday’s fields

Jeff Nelligan • July 31, 2019

This autumn Saturday, more than 3,400 NCAA football, soccer and rugby teams will meet on fields throughout the nation. More than 846,000 high school soccer players will play this week, along with an even 1 million high school football players on approximately 13,800 teams.

Factor in 2.3 million youth soccer players and 1.2 million youth footballers – and then consider the tens of millions of total spectators.

These are staggering numbers of participation and competition – there is no voluntary endeavor like it in American society today.

I know these Saturdays well. Because for the past 18 years, I’ve spent every single one of them on a field. My three sons have played on various athletic teams - nearly three seasons every year - from the ages of 4 to 22. Indeed, many weekday afternoons I attended a practice or a game or drove to one or the other; then, there were the dozens of tournaments and college recruiting camps, from Maine to Florida. In this age of big data, I recently calculated that collectively, my kids played on approximately 147 teams, attended more than 8,700 practices, and played in more than 2,300 games.

But I’m hardly alone: Three out of four American families with school-aged children have at least one playing an organized sport — a total of about 45 million kids; 61 percent of boys’ ages 6 to 12 play a team sport. It’s even higher for females at 64 percent.

Certainly athletic participation occasions the usual tropes: discipline, personal satisfaction, alertness of mind. For example, as the Women’s Sports Foundation notes, female high school athletes are 92 percent less liked to get involved with drugs, 80 percent less likely to get pregnant, and 3 times more likely to graduate than non-athletes.

But there’s a deeper benefit. As a supercharged, 4th-grade lacrosse coach once lectured me and other parents sitting in bleachers on the eve of what he called “a make-or-break” season: “Folks, this field is the only place your Johnny puts himself out there to be judged by a bunch of strangers. And half of them want him to fail.” Coach Firebreather could have been talking about almost any young person on the fields today.

And amen to that. In an age of adolescent relativism and softness, on-field competition is where Johnny succeeds or fails, and he does so in direct relation to his preparation, resilience, and teamwork. No excuses. There’s no app for grinding.

Twenty-three hundred games later, what I recall most is the adversity: My kid in the soccer goal stopping 23 shots, but allowing another eight to get by; a kid fumbling near the goal line and losing a championship game. And oh yeah, a kid never leaving the bench, even in the fourth quarter of a blowout game. Kids choked up, parents dismayed, coaches in shock, the echoes of cheers from the winning team and crowd - all of it excruciating.

But I know that the recovery from disappointments made my boys much stronger than the elation of victories. And today, I bet few of the spectators today, except for parents, have even an idea of what it takes to play on an NCAA Division I team, even a Division III squad. As the NCAA notes, “Of the nearly 8 million students currently participating in high school athletics in the United States, only 480,000 of them will compete at NCAA schools.” What the NCAA left out was that maybe one fourth of those competing will get much playing time. I know. Firsthand.

Ultimately, rewarded by grinding, one son played four years of Division-III lacrosse on a team that twice had a Top 20 ranking in the ESPN/Nike College poll; another was cut from a Division I football team and played on a club lacrosse team that won a national championship. The third is the only one to break through to D-1, playing rugby, though he will be in that “three-fourth’s” participation category.

However, this Saturday will be the first time in 18 years in which I’m not on a field somewhere, enjoying the athleticism and sweat and rugged American competition. And, yes, the adversity. That’s because exactly one-half of the millions of young people on the fields today will be on the south side of the final score.

But that doesn’t really matter. They’re out there, being judged, even if it isn’t a make-or-break season.

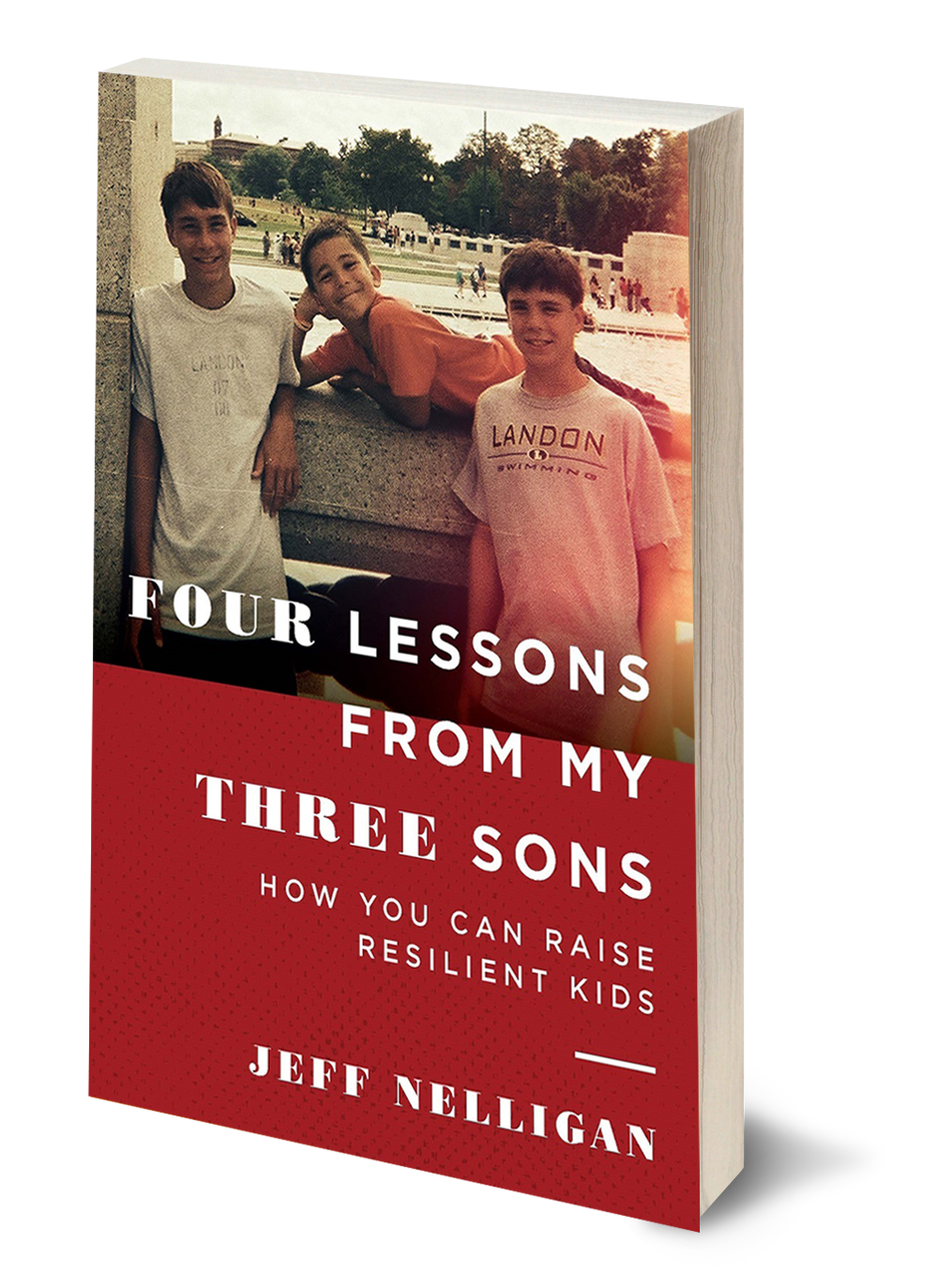

ABOUT THE BOOK

Every Dad in America wants to raise a resilient kid.

Four Lessons from My Three Sons charts the course.

Written by a good-natured but unyielding father, this slim volume describes how his off-beat and yet powerful forms of encouragement helped his sons obtain the assurance, strength and integrity needed to achieve personal success and satisfaction. This book isn't 300 pages of pop child psychology or a fatherhood "journey" filled with jargon and equivocation. It's tough and hard and fast. It’s about how three boys made their way to the U.S. Naval Academy, Williams, and West Point – and beyond.

It's 8:30 a.m. on a humid August Tuesday and I’m on the roof of the U.S. Capitol, the Dome rising 280 feet directly above. In my arms is a stack of thin boxes and I’m navigating a plywood gangplank leading to a rusted 15-foot flagpole. A colleague joins me carrying more boxes. She opens one and hands me a 2’ by 4’ American flag which I affix to the pole’s lanyard, raise and lower quickly, unfasten and hand to her as she hands me another. A third colleague brings out more boxes and retrieves the ones containing flown flags. This little dance continues for three straight hours. Afterwards, my colleagues and I carefully re-fold each flag and affix to it a “Certificate of Authenticity from the Architect of the Capitol” reading “This flag was flown over the U.S. Capitol in honor of____” and fill in the blank: “The Greater Bakersfield, California Chamber of Commerce”…the 80 th birthday of Wilbert Robinson of Bowie, Maryland, proud veteran of the Vietnam War…” We will perform this task for five days a week until Congress returns from recess. This is my very first job in Washington, D.C. and obviously, I have what it takes. *** Flag duty began my 32-year run in politics and government, which ended last week. It included four tours of duty on Capitol Hill working for three Members of Congress, two Presidential appointments serving Cabinet officers in the Departments of State and Health and Human Services, posts at two independent agencies, and a career position at FDA. The jobs were a mix of purely political positions where being on the south side of an election meant cleaning out your desk and getting good at catchy LinkedIn posts – twice that happened - and career federal government stints where the stakes were less exhilarating. *** I worked principally as press secretary and special assistant. The former job, a common D.C. occupation, was transformed in 2008 with the onset of social media, morphing from daily pronouncements of your boss’s wisdom on the issues of the day to rapid-fire postings on the obvious unreasonableness, even cruelties of your opponents. Sound familiar? As for the latter occupational specialty, special assistant, the terms ‘bagman’ or ‘fixer’ are more apt: A guy always two steps behind the principal but always ready to step up and fix whatever problem arose in daily political life. Need a special vegan lunch for Congressman Busybody, White House tour tickets for the Big Bad High volleyball team, or the personal phone number of the executive assistant to a heavy-duty lobbyist? I was your guy. Every leader needs a fixer. Like anyone else who works in D.C., I occasionally participated in a glam political moment – you know, that unique, epic event that would never ever be forgotten in D.C. history Until it was. *** The best part about government life was working for many men and women who were at the top of their game in the D.C. Swamp, one of the toughest arenas on the planet. Their success, from the vantage point of your humble correspondent, was attributable to four simple rules of life. “If you can’t measure it, it didn’t happen.” Every office I was in kept metrics on virtually every aspect of the principal’s week – how many meetings and events attended, X posts, interviews, committee votes, constituent letters, action items completed from memos?! Numbers, numbers, and always keeping score – and always the quest to improve. “Never lose it.” In a lifetime of political jobs, I may have heard a boss raise her or his voice half a dozen times, even during and after major-league setbacks. Self-control was their hallmark. One boss, a powerful House Committee chairman once confided to me, “I’m fine that 80 precent of my job is humoring these guys, no matter how crazy they get.” An equally valuable corollary skill: Humility. The ability of these individuals to admit to colleagues and staff when wrong on a particular issue. Which counterintuitively only upped their long-term credibility. “Something’s always gonna go south.” Always the need for a plan C. Every initiative during an upcoming day was scoured for what elements would interfere and how, if they occurred, they could be ameliorated. Hence, in the rare times when things did go south, there was always preparation in advance for getting to 80 percent of what was needed. “Good is not good enough.” Successful politicians and government leaders – and their staffs – never get complacent. If they do, they’re not long for the Swamp. Everyone is always hustling for the edge. A useful corollary learned from an NCO when I was in the Army: Always have your hand up. Volunteering is at the heart of the hustle, the cheerful willingness to take on the new and unknown and do whatever it takes. *** And that’s how it all started. On the second day of my first congressional tour the Member solicited volunteers “for a fun recess job that’ll get you out of the office.” It was flag duty and from that day onwards my government career could only go up. *****